The Oslo Philharmonic has had several tours to the Far East following its very first tour to Japan in 1988. The most recent tour to the region − to China and Taiwan − took place in the spring of 2017.

Chief Conductor Vasily Petrenko led four concerts in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and Truls Mørk was the soloist for all the concerts, playing Dmitri Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1 and Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto.

Ingrid Røynesdal, Chief Executive of the orchestra, described the tour in a travel column on the orchestra’s website:

“The Hong Kong Arts Festival is a prominent cultural event which extends over five weeks. The city is wall-papered with signs and posters; an aesthetic which may seem a little chaotic to our eyes. Still, the many advertisements and photos of the Oslo Philharmonic, up for many weeks, make for a unique communication on our native city and Norwegian cultural life.

The music of Jean Sibelius has also been important to the orchestra for many years. The fact that we come bearing Nordic music is deeply appreciated here: we also perform the music of Geir Tveitt (Hardingtonar), and Edvard Grieg, as well as Sibelius’ second symphony.

The countries in this region might be described as “younger nations” when it comes to the development o classical music. Yet, they are all the more vital for it. We were told by one of the promoters that in the Far East, it is mostly younger people who attend classical music concerts. Hearing Grieg’s music playing through the loudspeakers as we arrived at our gigantic hotel in Taipei yesterday evening was in every way a unique experience.

After two concerts for almost 4000 people in Hong Kong, accompanied by a literally roaring enthusiasm, the two concerts in Taipei were next. Nearly twenty journalists were present at the press conference following our arrival in Taiwan”.

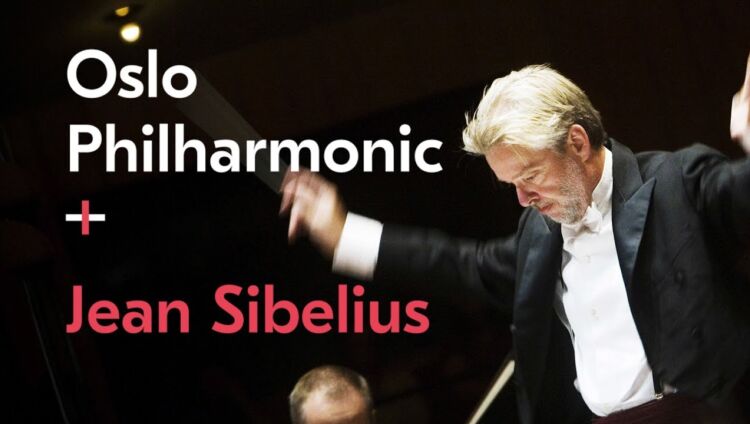

Watch the Oslo Philharmonic perform extracts from Sibelius’ Symphony No. 2 at the National Concert Hall in Taipei.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Vasily Petrenko conducted the Oslo Philharmonic for the first time in December 2009, with Edward Elgar’s Violin Concerto and Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 on the programme. A critic described his experience of the concert in Aftenposten:

“…Petrenko’s interpretation sets itself aside from all others I have heard of the Fifth symphony in an almost brutal fashion. Even the lyrical and ethereal parts were passionately formed in a way which I have never experienced before.”

Petrenko provoked great enthusiasm also from the musicians. When the time came to find a new music director, he was a clear favourite, and the news broke in February 2011: Vasily Petrenko was to take over as Principal Conductor from the autumn of 2013.

There was enormous interest when, just a few days later, on 19 February, Petrenko squeezed in an extra concert with the orchestra, performing Tchaikovsky’s fifth symphony:

“It was as crowded as if the Wine Monopoly had announced its closing down sale. It seems a few more people are hoping to get in, we heard drily from one of the many who were obliged to turn back empty-handed in the ticket office, while a number of hopefuls pushed and shoved in the hope of sneaking into the last free seats in Oslo Concert Hall”, wrote Aftenposten the following day.

Since he took over as Principal Conductor, Vasily Petrenko has led the orchestra in a number of tours in Norway and beyond, in addition to leading countless outstanding concerts in Oslo Concert Hall. The orchestra has made several critically-acclaimed recordings with him, not least a series featuring the music of Alexander Scriabin.

During the last few years, Vasily Petrenko has consolidated his position as one of the leading conductors of his generation. In 2017 he was named “Artist of the Year” by Gramophone, and in 2018 he made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

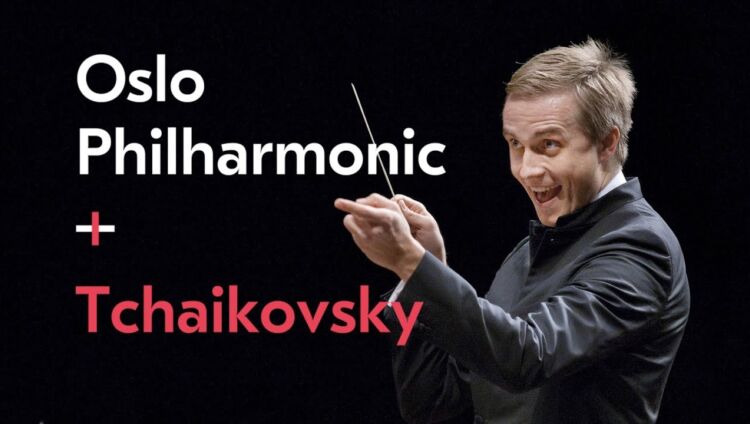

Watch Vasily Petrenko and the Oslo Philharmonic perform Tchaikovsky’s fifth symphony from 2011 here:

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Jukka-Pekka Saraste was twenty-seven years old when he conducted the Oslo Philharmonic for the first time, at the Freia concert in September 1983. Composer Johan Kvandal gave him top marks in his review in Aftenposten:

“The young conductor maintained excellent tempi; primarily not too fast in the first movement, and he displayed a considerable feel for the character and nature of the music. On the whole it was a fresh and clear performance which was warmly received, creating a dynamic atmosphere in the hall”.

In August 1985, Saraste returned to conduct music by Mussorgsky, Mozart and Sibelius. Jarle Sørå wrote in a review in VG:

“The party started with Pohjola’s Daughter, where Finnish conductor Jukka-Pekka Saraste proved that the music of Sibelius is in his blood. The music’s primal intensity and roughly-formed architecture was expressed with particular power.”

In an interview in Dagbladet with the title “The Finnish international star with a baton”, he is cited as follows regarding the orchestra’s phenomenal development under Mariss Jansons:

“Norway needed a chief conductor, and now you have one. The Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra is one of the leading orchestras in the world, and its musicians keep giving and giving”.

Jukka-Pekka Saraste was named Principal Conductor of the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra in 1987 and Music Director of Toronto Symphony in 1994. After many busy years and a shortage of time for guest conducting, he was warmly welcomed back to Oslo in 2001 by both the orchestra and the public. After this he returned regularly.

Five years later, it was Jukka-Pekka Saraste’s turn to become Principal Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic, in the season 2006-07. The choice garnered a great deal of interest both at home and abroad. Touring offers streamed in from both international and Norwegian promoters. VG’s critic Tori Skrede described one of his concerts in September 2007 as follows:

“When The Firebird by Stravinsky sounded in the hall on Wednesday night, every expectation was met. What sound! What dynamics, what power right down to the softest pianissimo! What an orchestra Saraste holds in the palm of his hand: it’s always equally impressive to watch when he stretches out his arm and virtually pulls towards him an incredibly tight, fully-formed sound from a group of more than a hundred individuals”.

Over the years, Saraste has received praise for his artistic depth and integrity. Throughout his career he has paved the way for including both older and newer Nordic music in the international standard repertoire, while being a leading international conductor within the great European orchestral tradition.

Jukka-Pekka Saraste’s concerts of Gustav Mahler’s symphonies have also been notable, and in 2013 he received the Music Critics’ Prize for his farewell concert with the Oslo Philharmonic, performing Mahler’s Symphony No. 2. The jury justified its decision as follows:

“Throughout the last seven years, Saraste has given us many great musical experiences. On this May evening, we were given yet another auditory demonstration of how he succeeds in lifting the orchestra up to a level that seems almost impossibly high. In Mahler’s second symphony there are also singers, both soloists and choir, and he succeeded in a masterful fashion in making these glide in as a completely natural part of the overall sound”

Jukka-Pekka Saraste was named Conductor Laureate of the Oslo Philharmonic in 2013, and has conducted the orchestra regularly since.

Watch Jukka-Pekka Saraste conduct the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra in Jean Sibelius’ Symphony No. 5 here:

André Previn was Chief Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic in the years 2002−2006.

Previn (1929−2019) had a musical career which can not be compared to many others. From the 1950s onwards he worked as a composer for film, and by the age of thirty-five he had already won four Oscars for his music. Since then, he has won altogether ten Grammy awards across different genres.

His conducting career took off in the 1960s, and he had great success as Principal Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, among others. He wrote copious amounts of music for symphony orchestra while at the same time making his name as an eminent jazz pianist.

Previn’s relationship with the Oslo Philharmonic started in the 1990s. Former Chief Executive of the orchestra, Trond Okkelmo, described how it all began in his tribute to the conductor following his death in early 2019:

For several years during the 1990s, the orchestra made attempts to invite him as a guest conductor, and when he finally accepted the invitation, he had to cancel due to heart problems. His interest in the orchestra had been awakened after having heard Mariss Jansons’ recording of Mahler’s second symphony.

After Jansons’ departure in 2002, the orchestra considered several conductors as its new Principal Conductor, but no one thought of Previn − perhaps he seemed somewhat out of reach. When he finally came to conduct the orchestra in Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, it proved to be an eye-opening experience for even the most experienced of the musicians. Also critics were enthusiastic. Previn reciprocated by expressing a wish for a closer relationship with the orchestra. He was asked how close he wanted the relationship to be and his response was “Why not as Chief Conductor?”

Few figures in Norwegian music life have had bigger shoes to fill than Previn had when he took over from Mariss Jansons, after a tenure of twenty-three years. But the combination of him and the orchestra proved to be an attractive one for concert arenas around the world.

The season 2004-05 was the greatest touring season with Previn: in August the orchestra played at the BBC Proms and at the Lucerne Festival, in October in Vienna’s Musikverein and in March in the United States on the occasion of Norway’s 100th anniversary as an independent nation, visiting Chicago, Washington DC, New York’s Carnegie Hall and Philadelphia. World-renowned violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, who was Previn’s wife at the time, was the soloist on the tour.

His period in Oslo might have been compromised by his failing health, but he still left behind many inexorable impressions and memories. Both musicians and public had the opportunity to experience him as the eminent musician he was − also as a pianist and chamber musician.

The day following André Previn’s death, the musicians of the Oslo Philharmonic paid tribute to their former Principal Conductor with a minute of silence. Some of the musicians who had worked with him described him in the following words:

“A fantastic musician”

“He could get an incredible sound out of the orchestra”

“He was very witty, and always made humorous comments on the podium”

“A genuine and honest musician”

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

The Oslo Philharmonic has been performing regularly in the world’s greatest concert arenas since the 1980s. In 1985, the orchestra visited one of the most prestigious halls in the world: Vienna’s Musikverein, which is known for its New Year’s concerts with the Vienna Philharmonic.

The first concert was a success, and since then there were many more. For the Oslo Philharmonic, one visit still stands out: its residency in the hall in 1997, where it performed on five consecutive nights.

Playing in the Musikverein is a privilege, and performing there for five nights in a row is a rare event usually reserved for orchestras of the highest level. The Oslo Philharmonic had the opportunity to do this, receiving standing ovations night after night, as well as glowing reviews. Many of the orchestra’s musicians count this week as being one their greatest experiences with the orchestra.

Following a number of years with many successful tours and recordings, it was somewhat difficult to communicate to the orchestra’s local environment how great this event actually was. Terje Mosnes succeeded in describing it in words in Dagbladet, and wrote the following just before the Vienna residency, under the title “Greater than we can grasp”:

“Since this isn’t about rock music or football, most of us might have some difficulty in understanding how big this is. Yet, when the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra and its Music Director Mariss Jansons embark on their residency in Vienna’s Musikverein this coming Monday, it’s as if Rosenborg has won the World Championship, or as if a Norwegian rock band has been voted into Rock n’ Roll’s Hall of Fame. There can hardly be clearer international recognition than this of a symphony orchestra which is now destined to be “Mariss’ band” (…)

The institution Musikverein, best known for viewers across the world for its annual New Year’s concerts, is the home of the Vienna Philharmonic, and apart from the Berlin Philharmonic, there aren’t many other orchestras who hold residencies in this richly embellished home of the European classical tradition (…)

The story which is known as Mariss Jansons and the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, which still has new chapters being written about it listing award-winning recordings, will endure, as it is not based on flighty luck alone. Talent, enthusiasm and many years of hard work form the background for the success over the last few years − for an orchestra, a conductor and an administration which have never fallen for the temptation to stop and look back in satisfaction, but have always raised the bar yet a level higher following every triumph”.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

From its inception in 1919 the Oslo Philharmonic (then known as the Orchestra of the Philharmonic Association) had 53 musicians. As late as the 1940s, the number of permanent musicians was 57, but after a campaign to increase this number in the spring of 1948, the size of the orchestra was increased to 63 musicians.

In the next decades, the number of musicians increased steadily. In 1960, the orchestra counted 69 musicians, and in 1979 it was 77. In the same year, an official investigation took place which was intended to set a direction for the public funding over the coming years. Following this, it was stated that the desired number of musicians was 96.

Mariss Jansons started as Principal Conductor in 1979, and threw himself headlong into a battle for additional musicians. In the beginning, things were slow to change − in the following year, the state budget allowed the orchestra to be increased by only two new positions. In his series of articles printed in Aftenposten in 1984, Jansons wrote:

“I must confess that when I am asked about the orchestra in other countries, I never admit that it is not complete. I’m ashamed to admit it. It does not command respect to say that the capital city in a country like Norway, and in our time, does not have a full symphony orchestra. And what’s worse, it is the only capital in Europe in this situation.

No one knows what I go through because of this, and what the orchestra’s musicians go through. It wouldn’t occur to anyone to send a football team onto the pitch with only ten players, or to simply remove three competitors from a ski racing team. Why should a symphony orchestra exist without having full forces at its disposal?”.

The Friends Association started a campaign in 1981 with the aim of collecting funds for new positions. “Action 81” was successful in collecting a considerable amount on money, and contributed to creating temporary positions which strengthened the orchestra in the course of the 1980s.

At this time, the number of musicians was not only a financial problem. Public funding was allocated by individual position, and hiring a musician could only be done following official state authorisation. Still, the authorisations arrived, slowly but surely, and in 1991, the number of permanently employed musicians was 101.

In 1995, the Oslo Philharmonic was reorganised to become a national institution, which received funding from the Department of Culture alone (in earlier days, the city of Oslo had also been a source of funding, as had been broadcasting fees from the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation). Now, a budget framework was in place, so that positions could be created without taking quota systems from funding institutions into account.

In this way, the orchestra could, to a greater extent, decide how to utilise its own means. This was not the solution to every problem, however − but the number of musicians was at least not limited. From the year 2000, the number of musicians in the orchestra has remained stable at 106 − twice as many as when the organisation was founded in 1919.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Throughout the first decades of its history, the Oslo Philharmonic only performed a few concerts outside Norway. After some major regional tours within the country in the 1950s, the orchestra left for its first European tour in 1962, and embarked on its first tours of the United States in the 1970s.

In the 1980s, the ground was prepared for a whole new level of touring activity than ever before. Mariss Jansons had taken on the role as Principal Conductor with a clear vision of how the Oslo Philharmonic would achieve international recognition, and together with its recordings, touring was to be a key method through which to attain this goal.

When a symphony orchestra is considered to be an unknown entity in the great music nations of the world, doors to the most important concert stages do not automatically open. The Oslo Philharmonic’s tour to the United Kingdom in 1982 was in this way a sort of test which might open up for new possibilities.

Fortunately, the orchestra passed the test with flying colours, and when it returned for a new tour in the autumn of 1984, both concert stages and everything surrounding the orchestra had received an upgrade. The orchestra arrived armed with a trump card up its sleeve: the fresh Tchaikovsky recording with Chandos.

The start of the tour − in Middlesborough − involved a poignant experience. At the beginning of the rehearsal, the orchestra was told that Arvid Jansons, Mariss’ father and a beloved conductor of the orchestra, had passed away earlier in the day in Manchester. After a minute of silence, the musicians completed the rehearsal and the first concert of the tour, with 1300 listeners present.

On 3 December, the orchestra completed its tour of the United Kingdom in London’s Barbican Hall. The British press published excellent reviews of the concert, and the tour was described in the Norwegian press as a triumph. The resonances from the success of the tour lasted until the end of the year: King Olav V mentioned the tour as an example of that it had been “a great year for Norwegian music” in his new year’s speech that year.

The following year there was a tour to West Germany, Switzerland and Austria. On this occasion, the most important destination was Vienna, where the Oslo Philharmonic was to perform for the first time in Musikverein; home of the Vienna Philharmonic and its New Year’s Concerts − and one of the most prestigious stages in the world for classical music.

Aftenposten printed the following comments prior to the start of the tour:

“The tour of seven German cities, among them Frankfurt, Mannheim and Essen, has been a success, with splendid reviews throughout, full houses and a warm response from the public”.

“But Vienna will be the big test”, Mariss Jansons told Aftenposten.

“No city has a comparable relationship to music than that of Vienna, and no concert hall such a knowledgeable and critical audience. There you’ll see audience members following the concert holding their own scores”.

“The growing reputation of the orchestra has spread to Vienna, and the concert is sold out to the very last seat”.

“I feel an enormous responsibility for presenting the orchestra in Vienna, and am very excited”, says Mariss Jansons.

Both audiences and critics gave the conductor and orchestra a very warm reception. According to Aftenposten’s journalist on the scene, concertmaster of the evening, Terje Tønnesen, described the experience as follows:

“Fantastic from beginning to end…this is a magical hall, and it has a magical audience. It’s astonishing how much they know about music! We felt as if the audience was our family; an equal partner. That struck me the most”.

In the course of the 1980s, international tours were an annual event for the Oslo Philharmonic. It rose to new challenges in the years to come: a tour to the United States in 1987 and the orchestra’s first tour to Japan in 1988 − where the orchestra was met with as great an enthusiasm as they had been met with in the West.

Mariss Jansons was sitting in the bus with the orchestra musicians as it drove through London during their UK tour in 1984. When they passed the Royal Albert Hall he turned around and shouted: “We’re playing there some day!”, and was met with expressions of humorous disbelief from the musicians. Three years later they entered London’s biggest concert arena for the first time − and not for the last time.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

In the late autumn of 1984, a collection of unusual articles appeared in Aftenposten. In a series of four articles, each of which covered an entire page of the paper, the Principal Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic, Mariss Jansons, sought to share his ideas with the public under the title “The Problem of Art in Norway”.

At this point, nine years had passed since his first engagement in Oslo, and five years since he became Principal Conductor. He introduces his first piece like this:

“For a long time, I reflected upon whether I had a moral right to write this article. I felt unsure if readers would understand me correctly, whether it would create a feeling that here comes this Jansons, a foreigner, criticising a country other than his own, forcing his own thoughts upon us”.

But every time I posed myself this question, I answered it: I am not really critiquing; I simply wish to express my observations and desires, and I am not forcing them upon anyone.”

After underlining the great meaning of art in his first article, he starts his second article stating concretely in which areas he believes Norway ought to prioritise the arts more highly, not least in the sphere of music. After a paragraph concerning the low wages of the musicians, he dwells on his relationship with the orchestra he stands at the helm of:

“Yes, I care about my musicians − because they deserve it. I am prepared to do everything possible for their welfare. Besides, it is my duty as Principal Conductor. In the way in which a father cares about his family, every leader should consider the people he is working with”.

Mariss Jansons’ statements on leadership were what led to much of the debate surrounding the series of articles, and the interest which was subsequently piqued in the business world regarding the orchestra and its conductor paved the way for future sponsorship.

Another topic which sparked debate was Jansons’ opinion that talent wasn’t being actively cultivated in Norway. He suggested a special school for children from the age of seven to seventeen, where they would have access to the best possible musical education. Cultivation of talent was a controversial theme, something the writer had been made clearly aware of:

“When I first suggested this idea, I heard that this would be an impossible proposition in Norway; that this would give privileges to one group of children and that this stands in opposition to the principles of the country (…)

Yet in art, and I’m not just thinking about art, it’s impossible to treat every individual equally. One has a talent for one thing, another for another thing. The fact that one person is occupied with something he has a talent for, does not imply that he is privileged or denigrates another’s worth or rights”.

Although not all the ideas expressed in these articles were convincing to readers, they succeded in creating a lively debate and attention surrounding the Principal Conductor of the orchestra. With his combination of dedication and candour regarding local cultural life, Mariss Jansons came to occupy a leading position in the Norwegian public sphere. He concluded his series hopefully, writing:

“Norway has every opportunity to raise the level of culture and art, and to create its own traditions…”

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

The Oslo Philharmonic started recording regularly already in the 1950s and in the decades which followed, produced a large amount of varied recordings under various labels. In the 1980s, however, the orchestra was to experience a recording success hardly anyone had dared dream of.

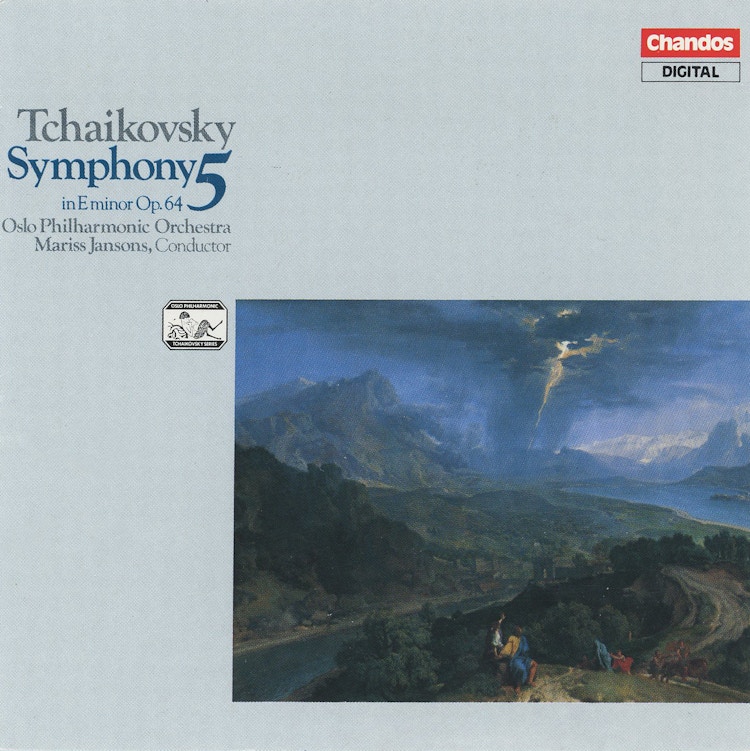

In 1983, Principal Conductor Mariss Jansons and the orchestra made the decision to embark on a project: they recorded Tchaikovsky’s fifth symphony as a demo, with the aim of securing a recording contract with an international label. Neither conductor nor orchestra received any payment for this.

Orchestra producer Terje Mikkelsen and orchestra chairman and viola player Oddvar Mordal travelled to London with the aim of presenting the fresh Tchaikovsky recording to different labels. And they succeeded − with the small but respected label, Chandos.

Chandos Records was founded by Brian Couzens as late as 1979, but had already achieved recognition for its recordings of high quality, not least the quality of its sound. The company entered into a contract with the Oslo Philharmonic to record all Tchaikovsky’s symphonies. Thus, Chandos became part of the orchestra’s success story − and vice-versa.

The meeting was summed up in Brian Couzens’ obituary in The Telegraph in 2015:

“When, in 1984, two Norwegian orchestra executives handed Couzens a cassette of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No 5, he was so impressed by it that the next day he signed Mariss Jansons and the Oslo Philharmonic to the label, making household names of them both.”

The first CD, featuring the fifth symphony, was released in the autumn of 1984. The release was well-timed to coincide with an ambitious tour of the UK. The orchestra had sought to build up its reputation in England through a tour two years earlier, and it now returned to perform at a series of attractive concert venues.

That the Oslo Philharmonic had made its debut in the international recording market was news in itself, and interest from Norwegian press did not abate when positive reviews started appearing internationally. In the winter of 1985, Edward Greenfield wrote in leading British music magazine Gramophone:

“Mariss Jansons and the Oslo Philharmonic won glowing notices after their recent concert at the Royal Festival Hall in London, and now I can understand why. (…)

The Oslo string ensemble is fresh and bright and superbly disciplined, while the wind soloists are generally excellent with an attractively furry-toned but not at all wobbly or whiny horn solo in the slow movement.

The Chandos sound lives up to the extremely high reputation of that company, very specific and well-focused despite a warm reverberation, real-sounding and three-dimensional with more clarity in tuttis than the rivals provide.

This first issue in a projected Tchaikovsky series from Jansons and the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra could hardly be more promising. All round there is no current rival quite to match this: a warm recommendation …”

Greenfield was also enthusiastic about subsequent recordings, and he later described Jansons (also in Aftenposten) as one of the world’s best conductors. He was of the opinion that the Oslo Philharmonic was on the level of the world’s best orchestras − perhaps with the exception of the Vienna and Berlin Philharmonics at their best.

The orchestra was soon faced with a difficult choice when it received a unique offer from recording giant EMI. The ties with Chandos were strong, but the advantages EMI could offer when it came to distribution and marketing were convincing. The new contract was signed in the autumn of 1986, and in the next decade a string of new EMI releases was produced.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

On 19 June 1983, the first of the Oslo Philharmonic’s Summer Concerts in Holmenkollen was arranged, with Mariss Jansons conducting. This proved to be the beginning of a popular tradition which would continue into the early 2000s.

NRK’s Stein-Roger Bull had pitched the idea of this kind of concert as early as in the 1970s, but it was only in 1983 that the time was ripe: the year before, a world championship in skiing had taken place (the year when skiing champion Oddvar Brå had broken his pole) and the Holmenkollen infrastructure had just been through a thorough upgrade.

After the world championship in skiing was over, the Ski Association took on the role of promoter. “The cost of this would have been too great for NRK to shoulder alone, but with the support of the Ski Association, it has become possible to extend the athletics arena to an outdoor concert hall”, remarked Stein-Roger Bull in Aftenposten before the concert, where he was responsible for the content and direction.

The plans created great anticipation. VG reported:

“An enormous platform of 440 square metres is in the process of being built at Besserudtjernet in Holmenkollen. The platform on the ski slope will be the scene of a great cultural event on Sunday 19 June. The Philharmonic Association will play Norwegian music, and the concert will be broadcast on television to great parts of Europe”.

The project reflected international ambitions from the outset. The thought was that the Holmenkollen concerts should be Norway’s answer to Vienna’s New Year Concerts. With the ski jump in the background and the surrounding beautiful nature clearly visible, this would surely be a promotion for Norway of the best possible kind.

Following the Eurovision fanfare and the introduction to Grieg’s Symphony in C major, host Knut Bjørnsen welcomed the audience. Eight countries in total broadcast the concert, which in addition to the music featured images of bright sunshine and musicians in sunglasses, and a ballet choreographed by Kjersti Alveberg.

The first programme consisted entirely of Norwegian music. After an orchestral version of Christian Sinding’s Frühlingsrauschen, music from Grieg’s Peer Gynt followed, then Johan Svendsen’s Violin Romance performed by Arve Tellefsen, Ketil Hvoslef’s commission Air and music by Geirr Tveitt and Johan Halvorsen.

In 1985, during the third concert, a tradition started which was to last a long time: the concert was concluded with Johan Halvorsen’s Entry of the Boyars. For many, the sound of these tones evoke some of the most vivid memories from the Holmenkollen concerts.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

The Oslo Philharmonic celebrated their 60th anniversary with a festival concert in Oslo Concert Hall on 26 September 1979. The orchestra’s name was changed from the Orchestra of the Philharmonic Association to the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, and, as on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in 1969, a new Chief Conductor stood on the cusp of taking the helm − this time it was thirty-six year old Mariss Jansons.

Jansons had conducted the orchestra for the first time in 1975, and the meeting made an indelible impression on both conductor and orchestra (see separate article). It was clear early on that his predecessor, Okko Kamu, did not wish to extend his contract beyond the initial four years which had been previously agreed, and Jansons was a clear first choice as his successor.

In the anniversary booklet from 1994, Jansons describes his first impressions of the orchestra, and how everything was confirmed:

“From the very first moments of our meeting in 1975, I have known you as a professional ensemble through and through, with your own identity and unique sound, with an exceptionally strong work ethic and discipline, with an honest dedication, engagement and reverence towards your duties, without a trace of arrogance, superficiality or routine thought.”

Mariss Jansons was interviewed by NRK on the occasion of the anniversary concert in 1979. In answering the question as to what the duty of an artistic leader is, he offers answers which give some indication of the unique relationship he was to develop with the orchestra in the years to come:

“The artistic leader is responsible for the quality of the orchestra. He must think of the orchestra constantly, and work for it and not for himself. An artistic leader’s primary duty is to always think of the orchestra … as his own child. And that is a great responsibility.”

Furthermore, he was quite clear about one of his main missions as Chief Conductor:

“We only have one problem: the orchestra is too small. We have to fight hard, so we can grow to the same size as a great European orchestra. Sweden, Denmark and Finland − they all have full-sized orchestras, so why can’t Norway? It’s a question of prestige, and a question we all have a duty to consider”.

Significant progress was made in the following years with regards to this mission.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

In the spring of 1974, the Oslo Philharmonic crossed the Atlantic for the first time in order to tour the United States. The tour lasted nearly a month, and involved as many as twenty-four concerts along the West Coast. The pianist Jens Harald Bratlie was the soloist, and Romanian-Israeli Mendi Rodan conducted the concerts.

The media was far more present when the orchestra again travelled to the United States in 1978, this time to the East Coast. Once again, it was on the road for a whole month, from the first concert in Miami, via a series of cities in Florida, Alabama, North- and South Carolina, to the Kennedy Centre in Washington D.C, and the grand concluding concert of of the tour, in Carnegie Hall, New York.

The orchestra’s Principal Conductor at the time, Okko Kamu, conducted the concerts. Some were critical of the fact that Swedish pianist Staffan Scheja was the soloist in Grieg’s Piano Concerto, although Norwegian violinist Arve Tellefsen was also part of the tour − in Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane.

The fact that none of the twenty-four concerts contained music after Grieg’s time also provoked reactions. VG’s commentator, Jarle Sørå, even remarked: “The Philharmonic Association has let Norwegian contemporary music down completely during its US tour”.

The orchestra’s Director, Alv Rasmussen, explained the conditions for the tour in an article in VG, referring to the collaboration with the orchestra’s touring agent, CAMI:

“They wanted − how shall we put it − a Scandinavian profile for the programme. Grieg’s piano concerto was a must … In return they would pay the costs of the tour, and make all the practical arrangements in a professional way (…)

We had to agree to it. Without their financial and practical support, the tour would have cost us such a high sum that we would not have managed to cover it (…)

We are not doing this to enjoy a holiday in the United States. An orchestra of this importance needs to feel the air under its wings from time to time. It’s inspiring for the musicians to experience different conditions, and to play in concert halls other than their own, for different audiences”.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

In 1972, excavations for what was to become Oslo Concert Hall started in Vestre Vika. The start of this meant that the decades-long debate on where the hall was to be built, could be put to rest. It also meant that a proper concert hall was finally going to be constructed in Oslo, almost 120 years after violin legend Ole Bull started raising funds for the purpose.

The building period was far from free of conflict. In 1964, the estimated construction costs were 64 million Norwegain kroner, but this increased gradually to 258 million, which naturally led to furious discussion regarding the financing. The orchestra had no representatives in the Building Committee, which created friction regarding the following up of the orchestra’s needs in the new building.

The construction process was met with additional challenges. When the opening day drew close, an argument broke out concerning the programme for the inaugural concert. Should this principally consist of new Norwegian music or established classics? After a tough conflict with the Norwegian Composers’ Union, the orchestra accepted the first alternative.

On the morning of 22 March, 1977, the offical opening took place, with the Chairman of the Board of the concert hall, Brynjulf Bull, as the main speaker. “We come late, and we come at a cost − but we are coming, your Majesty!” Bull stated. He went on: “We have not grown poorer, but richer, in investing so much in this building. Future generations will thank us for it”.

In the evening of the same day, the Oslo Philharmonic performed the inaugural concert for a hall filled with celebrated guests, including the Royal Family. Principal Conductor Okko Kamu conducted Klaus Egge’s Symphony No. 2 and two prize-winning works from a composition competition held in honour of the opening: Opening by Oddvar S. Kvam, and čSv by Jan Persen. After the break, former Principal Conductor Øivin Fjeldstad conducted the orchestra in Johan Svendsen’s Symphony No. 2.

The Concert Hall’s inauguration programme continued throughout that week, and in the following weeks, activity in the house remained high. In its inaugural year, every household in Oslo was sent the folder “Come and Listen to our New Home” − a great communications effort for its time.

In the course of the first six months, 120.000 tickets were sold for various arrangements in the hall, and in the course of the first two years, the number of visitors had exceeded 400.000. There were to be numerous long discussions regarding the acoustics and other conditions in the years to follow. But that the hall was a popular success was indisputable.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

In the autumn of 1975, at the age of twenty-nine, Okko Kamu took on the position of Chief Conductor for the Oslo Philharmonic.

After having started his career as a violinist, he started conducting opera in his native Helsinki and in Stockholm, before becoming Chief Conductor of the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra in 1971. In 1969 he had won first prize in the prestigious Herbert von Karajan conducting competition.

From the very beginning, he had made it clear that his period as Chief Conductor was to last only four years, so when he in 1979 passed the baton to Mariss Jansons, it was quite devoid of drama. In the course of these four years, he became a much-loved figure both in the orchestra and in Oslo’s music life in general.

It was very clear, particularly around the time of his farewell concert, that Okko Kamu had found his way into the hearts of many. Morgenbladet reported the following:

“Not least in the current season, Kamu has been responsible for a series of memorable performances, and it is simply regrettable that the nation is about to lose a great musical personality who, through his expertise and strong work ethic, has become a respected figure among both musicians and the public”.

“During his time as the organisation’s permanent Artistic Director, this Finnish dynamo has brought the orchestra to a formidable standard − not least considering its modest number of musicians”, wrote Jarle Søra in VG of the same occasion.

Aftenposten’s Mona Levin remarked in the introduction to her farewell interview with the conductor:

“In the four years which have passed, Okko Kamu has grown to be such a familiar, well-loved figure in our musical life, that it will feel strange to be without him”.

Kamu himself explained in the same interview that he intended to distance himself from music for a while:

“In eight months’ time I intend to take a sabbatical. First I will try not to do anything. Then I will stay open for what the future brings”.

The future was to include positions in Birmingham, Copenhagen, Lausanne and in his native Finland, as well as several engagements as a guest conductor with the Oslo Philharmonic.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

In September 1975, the thirty-two year old Mariss Jansons arrived in Oslo for the first time. He was born in Riga and was the son of Arvid Jansons (1914−1984), an internationally acclaimed conductor with a fruitful and enduring relationship with the Oslo Philharmonic. He had been the first to indicate to the orchestra that his son was a promising conductor.

Mariss Jansons’ first engagement with the Oslo Philharmonic extended beyond three weeks, and included different programmes. In the first week, the orchestra played Serge Prokofiev’s music from Romeo and Juliet, and from the first note, the musicians noticed that there was something unique about the young guest.

Double bass player Svein Haugen relays the following about their first meeting:

“It was very unusual. There was something about his body language; the clarity of his beats, and of the music in general. A clear communication quickly arose between what we were doing and what he was doing. The precision in the orchestra got much better already from the first rehearsal.

He also demonstrated some formidable knowledge of detail in his instructions, for example when it came to matters of intonation and the building up of chords. We already knew his father as a very thorough conductor, and in many ways, Mariss continued that same school in his own work”.

The week following Jansons’ visit, the new Principal Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic, Okko Kamu, arrived for his first concert week with the orchestra. Kamu made a very good impression and grew popular both with the orchestra and with audiences. But he had signalled clearly in advance that he would not stay longer than four years, no matter how the collaboration went.

The following year, Mariss Jansons returned, and this proved to be yet another inspiring experience. Discussions started surrounding whether Jansons could be a possible successor to Kamu, and ultimately, one of the orchestra’s musicians, Reidar Hjelde, who was fluent in Russian, phoned Jansons directly. He could confirm that the interest was mutual.

Much detailed diplomacy was required in order to agree on the conditions of the agreement, not only with the conductor himself, but also with the Soviet-Russian authorities. Yet, in 1979, on the 60th anniversary of the orchestra, Mariss Jansons could begin his tenure as Principal Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic. It was the beginning of a unique partnership.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Miltiades Caridis was born in Gdansk in 1923, and grew up in Dresden with a Greek father and a German mother. After studies in Athens and Vienna, he worked in different German opera houses, from 1959 as conductor of the Cologne Opera. In the 1960s he also led the Hungarian exile orchestra, the Philharmonica Hungarica, and it was with this orchestra that he conducted his first concert in Oslo, in Folketeateret, in the autumn of 1963.

Two years later, he conducted the Oslo Philharmonic for the first time, and he returned both in 1967 and 1968. He began his tenure as Conductor and Artistic Director in 1969, after Øivin Fjeldstad had made it clear that he was withdrawing from the position. In a telephone interview which was printed in Aftenposten on 11 January 1969 on the occasion of the engagement, he tells of his preparations for the role as Chief Conductor:

“I am well aware of the fact that it’s a good orchestra. I grew to know the musicians well during the three concerts I led recently in November and December. I know my task will be demanding and interesting. New fields are to be ploughed, and I hope that having a foreigner like myself as director will be an advantage for Norwegian music life − someone who sees the situation from the outside, with an objective viewpoint.

The first thing I have done, is to request the Philharmonic Assocation’s general programmes for the last ten years. It is the line of direction which interests me. When I have immersed myself in the repertoire played in the last ten years, I will be able to see where it is beneficial or necessary to focus my efforts.”

Miltiades Caridis’ first concert as Chief Conductor was at the orchestra’s 50th anniversary in September 1969, and included Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. In the following year, the 25th anniversary of Bartók’s death was marked with two weeks of concerts featuring the composer’s music.

Caridis’ efforts to expand the orchestra’s repertoire was perhaps the most important footprint he left of his work in Oslo. Marit Gaasland, writing on behalf of the Oslo Philharmonic, sums it up in a commemorative article published at his death in 1998:

“Through Miltiades Caridis, Oslo’s audiences had their horizons significantly expanded. He introduced us to a series of composers who until then had been little performed in Oslo or not at all, such as Henze, Ligeti, Poulenc, Milhaud, Janácek, Walton and not least Bartók, who was his declared favourite”.

Of the more established composers, he offered a series of first experiences for the orchestra, such as Mahler’s third symphony, Bruckner’s eighth, Richard Strauss’ Alpine Symphony, and Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 14, which had recently received its world premiere.

Given Caridis’ background in opera, it was natural that vocal music lay close to his heart, and we think that many, both among musicians and the public, will remember with a unique joy his many and great performances within this genre”.

Caridis was also very interested in new music, and championed Norwegian composers, promoting the new writing of the younger generation as well as that of more established artists. In 1972, he was, together with the Oslo Philharmonic, awarded the first Norwegian Grammy Award (The Spellemann Prize) for classical music in the category “Serious Recording of the Year”, for a recording of Fartein Valen’s music.

Miltiades Caridis was a good linguist and learned to speak Norwegian fluently during his time in Norway, although he didn’t reside here. In 1975, he continued on to be Music Director of the Duisburg Philharmonic, but returned several times to Oslo as a a guest conductor. In 1981 he received the Béla Bartók medal for his work in promoting Bartók’s music.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

The story of constructing a new concert hall for orchestral music in Oslo is far older than the Oslo Philharmonic. As early as 1860, Ole Bull, the great violin virtuoso of his time, arranged three concerts with the aim of raising money for a new concert hall in his Christiania.

In 1918, the year before the Oslo Philharmonic performed its very first concert, shipping magnate A.F. Klaveness and his wife Therese donated 500,000 Norwegian kroner to the orchestra, which formed the basis for a concert hall fund. However, the following decades witnessed a string of discussions and decisions which did not yield any concrete results.

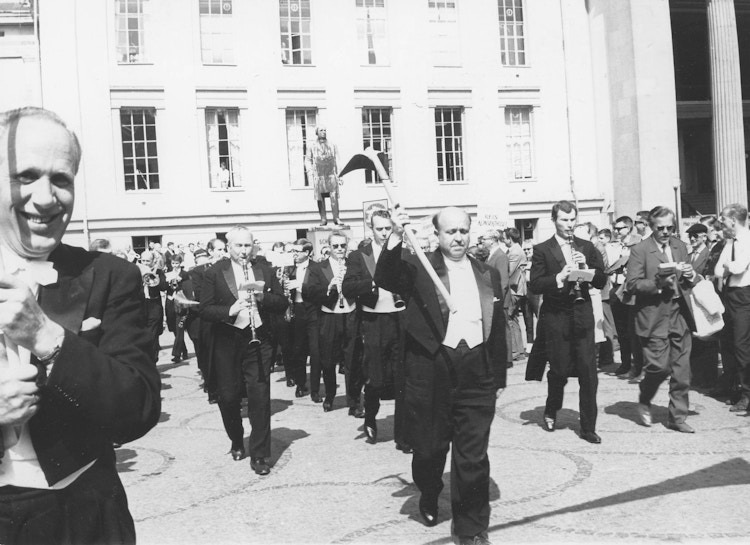

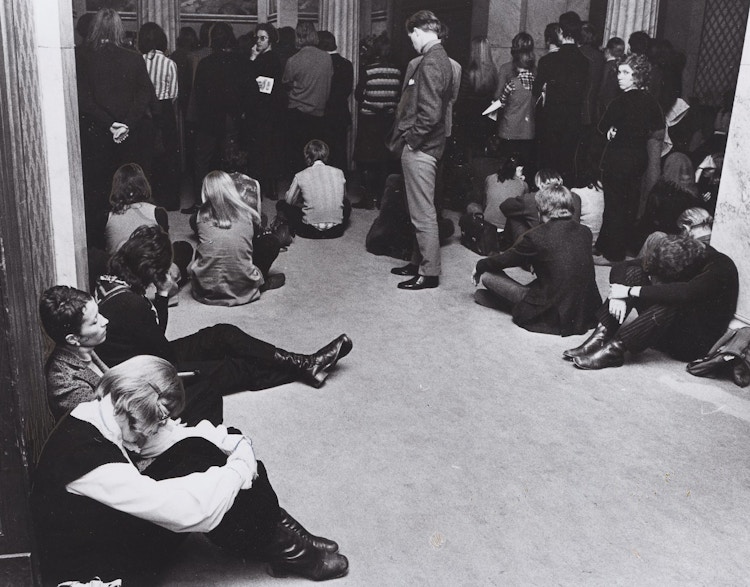

In the 1950s, however, things started to change. In 1955, an architectural competition was held in connection with plans for a new concert hall, and in 1957 a winner was announced: the Swedish architect Gösta Åbergh. It was the 10-year anniversary of this competition that the musicians of the Oslo Philharmonic marked with their demonstration in June of 1967.

The demonstration, including 70 musicians dressed in tails, went from the University Square and around the Town Hall, ending in the concert hall site in Vika, which was still a well-filled parking lot. There, they concluded their demonstration with performing the march Hiv ankeret!, and could thereby confirm that they had at least played on of the planned concert hall’s site.

The exercise had a big effect on the debate surrounding the issue. Mona Levin sums up the reactions to the demonstration in the Oslo Philharmonic’s anniversary yearbook from 1994:

“The demonstration was noticed by many, and was fully supported by the public as seen in the press, radio and television. In all years, both before and after the war, the Philharmonic’s administration and musicians have been enduring champions for the building of a new concert hall. Countless articles, chronicles, and comments have been penned and debated, countless reasons have been given for how an improvement of the orchestra’s working situation would benefit the common good. Now, the indefatigable pioneers of our music life can take comfort in the fact that also the general public demands a new concert hall”.

In December 1967, the foundation stone of Oslo Concert Hall was laid.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

On 9 June, 1965, the Oslo Philharmonic travelled from Fornebu Airport, Oslo, to its most far-flung international touring destination to date − Greece. The orchestra was invited to perform in the opening concert of the Athens Festival on 1 July with a concert in the Herodes Atticus theatre on the Acropolis.

Financially, the project was a challenge. It was calculated that the tour would cost 140,000 Norwegian kroner, and that the performance fee from the festival would only amount to 85,000. Nevertheless, the invitation created a great stir, and promised a myriad of possibilities for promoting Norwegian culture, and this opened up for the possibility of public funding for the remaining 55,000.

The orchestra’s musicians were unaccustomed to playing in the open air and in such a large amphitheatre, but the acoustics were excellent for the 5000 listeners. They had the opportunity to hear a varied programme directed by Principal Conductor Øivin Fjeldstad: Grieg’s Piano Concerto with Robert Riefling as the soloist, Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony, and a symphony by the recently deceased Greek composer Manoli Kalomiris.

The Greek reviews of the concert were very positive, and the critics praised the conductor’s interpretation of Kalomiri’s symphony in particular. There were also Norwegian journalists in attendance, who were able to communicate something of the atmosphere to their homeland. Veronica Reff wrote in Aftenposten:

“Never before has the Philharmonic Association had such an overwhelming response as it has experienced here in Athens. Never before has it delivered such a precise and dazzling performance as it did during the opening of the Athens Festival last night … Those of us present felt ourselves part of something quite outstanding, as we sat on the hard marble benches without a backrest, our backs nearly giving in, but we sat there with Norway in our hearts. It was as special as winning an Olympic gold medal”.

The following day, the orchestra’s other Principal Conductor, Herbert Blomstedt, conducted another concert, where Greek pianist Rita Bouboulidis performed Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 2. The orchestra also performed music by Arne Nordheim (Canzona per Orchestra), Harald Sæverud (Sinfonia Dolorosa) and Carl Nielsen (Sinfonia Espansiva).

The third and final concert of the tour took place in Volos, also in an old amphitheatre. The orchestra played Egil Hovlands Symphony No. 2 and music by Grieg, Weber and Brahms to a large and enthusiastic audience.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Øivin Fjeldstad (1903−1983) performed his first concerts with the Oslo Philharmonic (at that time known as the Orchestra of the Philharmonic Association) already as a seventeen-year-old in 1921, as a substitute in the violin group. Two years later, he had a permanent contract with the orchestra.

Fjeldstad eventually became one of the capital’s most outstanding violinists: he was engaged early on as Concertmaster of the Radio Orchestra of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) and as third Concertmaster in the Oslo Philharmonic. As a violin teacher and Head of Studies at the Music Conservatory, he was part of forming the next generation of orchestra musicians.

Øivin Fjeldstad made his debut as a conductor with the Oslo Philharmonic in 1931, and directed several individual concerts in the course of the 1930s. Yet, it was only after having studied with the legendary conductor Clemens Krauss in Berlin in 1939 that his conducting career took precedence over his other activities.

After the Second World War, Fjeldstad was constantly given new engagements. In 1946 he was engaged as Chief Conductor of the NRK orchestra, and he conducted a great deal of opera in the 1950s. In 1956, he conducted a well-known recording of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung which included Kirsten Flagstad, and in 1958 he became Music Director of the Norwegian Opera.

When Odd Grüner-Hegge left his position as Chief Conductor of the Philharmonic and the orchestra started advertising for his replacement, it received 96 applications from 21 countries. Øivin Fjeldstad was the sole Norwegian applicant, but he was also a well-deserving and popular conductor with the orchestra. Fjeldstad and Herbert Blomstedt (see separate article) shared the position from 1962−1968, and after this time Fjeldstad continued alone until he left in 1970.

In the course of the 1970s, Øivin Fjeldstad continued to serve both as guest conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic, as well as with international orchestras, and as leader of the Cæcilia Association and Vestfold Symphony Orchestra. In 1977, he conducted the inaugural concert of Oslo Concert Hall. Fjeldstad’s rich contribution to both Norwegian and international music life is summed up in Norwegian Biographical Encyclopedia:

“Fjeldstad’s inexhaustible contribution to Norwegian music life, which includes his work with popular music, opera, new music, amateur music and communication, was widely acknowledged and appreciated, and he was made a Knight 1st Class of The Royal Norwegian Order of St Olav in 1960. He also received international awards, including high Swedish, Dutch and Belgian orders, and in 1952 he received the Arnold Schoenberg prize for his contribution to new music”.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Herbert Blomstedt had just turned thirty-five years old and was already an established conductor when he started his tenure as Chief Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic together with Øivin Fjeldstad in the autumn of 1962.

Blomstedt had won a prestigious conducting competition in Salzburg in the 1950s and had studied with some of the greatest conductors of the time, including Leonard Bernstein. From 1954 until 1962 he was the Chief Conductor of Norrköping Symphony Orchestra.

Almost sixty years after he started as the orchestra’s Chief Conductor, Herbert Blomstedt remains one of the Oslo Philharmonic’s most dearly-loved guest conductors. In their biographies, many of today’s orchestra musicians mention Blomstedt’s concerts as counting among the highlights of their orchestral careers.

Blomstedt was also highly popular in Norwegian music life during the 1960s. In his farewell interview in Dagbladet on 28 March 1968, he is described as follows:

“It is as big a tragedy for Norwegian music life today that Herbert Blomstedt has taken on the position as Principal Conductor of the Danish Radio Symphony as when Johan Svendsen became Music Director for The Royal Danish Theatre ninety years ago. He has been an indispensable and life-enhancing inspiration during these last six years, and it isn’t just the Oslo Philharmonic’s musicians who are going to miss him, although they will feel the loss the most acutely”.

Herbert Blomstedt reciprocated with equal warmth when referring to the orchestra in the same interview:

“I wish I could bring the whole orchestra with me to Copenhagen. I am very fond of it; its ability, its blithe and positive can-do attitude … it’s a miracle that the orchestra works as well as it does, considering that it is undermanned and without a home”.

Blomstedt was referring to the ongoing battle for a new concert hall in Oslo as a primary reason for withdrawing from his position as Principal Conductor. However, he returned as a guest conductor already in the early 1970s, but then almost twenty years would pass until his next visit in 1992, when he conducted Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 9.

Violinist Arne Monn-Iversen, who had worked in the orchestra since 1953, described the concert as follows:

“The response to Blomstedt was overwhelming. We had always had the greatest respect for him, but this was still a very special week. He had asked for the original Mahler bowings, something we at first were not thrilled about as we had to change everything we had worked on. The resistance soon abated, and the rehearsal period was unforgettable.

We went deeper and deeper into the material, and felt truly inspired. On the concert evening, everyone’s concentration was sharp. Mahler’s bowings created, as they were intended, an elated mood. I realised that evening that Mahler was a genius − and Blomstedt too!”.

In recent years, Herbert Blomstedt has conducted the Oslo Philharmonic regularly. In the autumn of 2018 he was a guest in the "Orchestra Couch”, where he in conversation with NRK’s Mari Lunnan recounted numerous stories from his time in Oslo in the 1960s.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

The Oslo Philharmonic’s first European tour in November 1962 was an ambitious affair. In the course of sixteen days, the orchestra performed concerts in as many as twelve cities: Hamburg, Hameln, Heerlen, Hagen, Bonn, Amsterdam, Haag, Frankfurt, Berlin, Hildesheim, Kiel and Copenhagen.

Norwegian audiences and press followed the international response to the orchestra with great excitement, not least the reception in well-known music cities such as Hamburg, Berlin and Bonn. Concert reviews were very positive overall, and the tour was perceived as strengthening Oslo’s reputation as a musical centre.

Achieving recognition from the European music world as an orchestra on a high international level was a new and exciting experience for the musicians. “We didn’t know how good we were before we read about it in foreign papers!” mused a musician taking part in the tour.

The orchestra’s two new Principal Conductors, Herbert Blomstedt and Øivin Fjeldstad, took turns conducting. Two soloists were also part of the trip: Aase Nordmo Løvberg, who sang songs by Grieg and Wagner, and the pianist Robert Riefling, who played Grieg’s Piano Concerto and Beethoven’s third Piano Concerto.

All the concerts opened with Norwegian contemporary music: Bjarne Brustad’s Symphony No. 2, Harald Sæverud’s Galdreslå and Fartein Valen’s The Graveyard by the Sea, across different programmes. The second part of the concerts featured a Brahms, Beethoven or Svendsen symphony.

International critics reported their impression that the orchestra represented a unique Nordic sound which distinguished itself from its European counterpart. The tour resulted in a series of invitations to new destinations. Still, three years were to pass before the next international tour, which went to Greece.

(The quote from the musician is taken from the anniversary programme of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra on its 75th anniversary in 1994.)

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

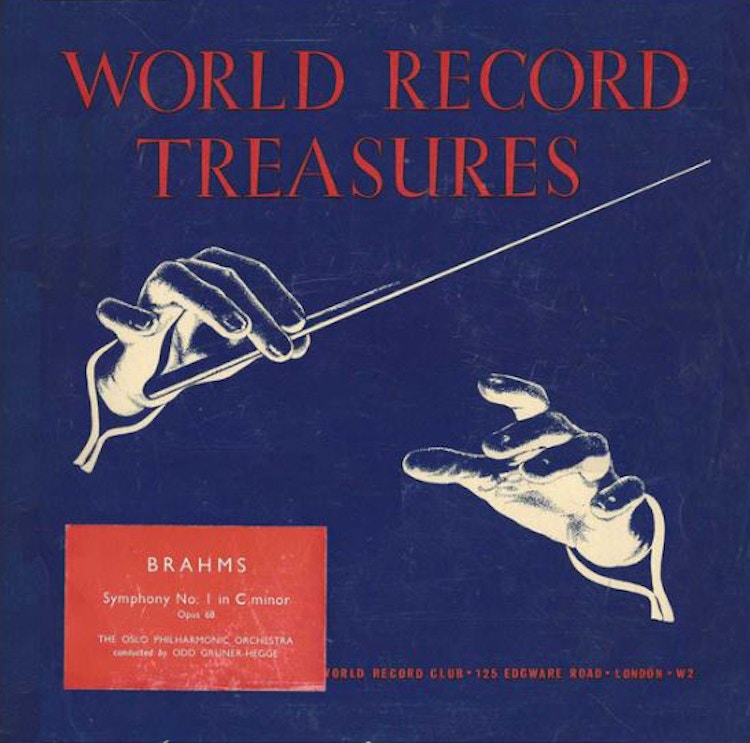

The Oslo Philharmonic made a great number of recordings in the 1950s, mostly for American record labels. For the label RCA Victor alone the orchestra recorded around 100 works, and the orchestra also collaborated with His Master’s Voice and Mercury.

A part of the recordings included the standard classical repertoire, but the orchestra also recorded quite a bit of newer American music. While Odd Grüner-Hegge and Øivin Fjeldstad conducted the classics, various guest conductors took the reponsibility for the American repertoire.

A conductor who frequently guested in Oslo during this period, was the Italian-American conductor Alfredo Antonini. He was the Music Director for the television production company CBS, and is described as follows in Aftenposten in June 1957:

“Alfredo Antonini … has become a fiery advocate of the Philharmonic after his experiences in Oslo. It’s far from trivial that a man in his position makes use of every opportunity to mention the speed and ability of our musicians when facing unknown modern composition. He has repeatedly confided that he knows no orchestra in the United States who can work as fast and as expertly with new music as they can”.

At the time, working on the recordings was considered to be something of a private matter for the musicians, and the orchestra had no system for keeping track of what was being recorded. With recordings taking place “after working hours”, a working day for a musician could easily extend from the morning until midnight.

Arne Novang, a cellist in the orchestra from 1945, is quoted in one of the orchestra’s anniversary programmes, discussing the first decade of recordings. “You know, being a musician in Norway at that time was not a job associated with status or high pay. We simply couldn’t afford to say no”.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

The English conductor Thomas Beecham (1879−1961) was one of the most famous conductors of his time. He was in addition a colourful personality about whom there were countless anecdotes. He was also no stranger to conflict − a number of his conductor colleagues bore a grudge against him − and vice versa.

The final concert in the Oslo Philharmonic’s season 1954/55 was led by Beecham. He conducted music by Handel (in his own arrangement), Mozart, Sibelius, Berlioz and his compatriot Delius, the latter a composer Beecham had a great part in making known.

Beecham’s visit on 19 June was one of the summer’s biggest events in Oslo, and it was followed by long-lasting applause. The conductor was known for his improvised, short speeches, and suddenly he made a sign to the audience to stop clapping. His speech was recounted as follows:

“I visited Oslo forty years ago, and people were talking about that, on my next visit, Oslo would have its own concert hall. I returned thirty years ago, and people were again talking about a new hall. Then I was here twenty years ago, and they were still talking about a new hall being built.

Now I’m here again, but there still isn’t a hall! Oslo should be ashamed of itself … (he flung open his arms). Now I won’t be back until a new hall hall is in place!!”

He later remarked to the orchestra’s general manager Eigil Beck: “I should rather have threatened to stay in Oslo until the concert hall is built”.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

The Philharmonic Association’s first three decades were musically harmonious, but financially tempestuous. The following decades saw some improvement, and some of the funding challenges was made easier when the Friends of the Philharmonic Association was founded in January 1952.

On the inaugural day, 7 January, the Association had 211 members. The following year, the number had increased to 411, and the Association now had members both from other cities and countries. During the 1990’s, the number of members increased to over 2000, and in the last decade the figure has been around 1000.

The first Chairman of the Friends’ Association was Nicolai A. Andresen, the grandson of the founder of the Oslo Philharmonic, A.F. Klaveness, and he kept his position until 1998.

The Friends’ Association quickly grew to be an important financial ally, and already in the same year the Association supported the orchestra’s regional tour to the north of Norway. Another important project which received support was the Youth Concert Series, held in the University Aula in the 1950s and 1960s.

Since its inception, the Association has also had a hand in supporting other efforts which have been a part of enhancing the reputation of the orchestra. During the 1950s and 1960s it supported engagements of conductors and soloists who were considered to have been too expensive for the orchestra.

During the 1980s, the Association contributed to touring and recordings with Mariss Jansons. It has also helped to acquire instruments, to better the acoustics of Oslo Concert Hall, with the continuing education of musicians and to purchase new concert attire − something it is also doing in connection with the current anniversary season.

Still, financial support is only one aspect of it − the symbolic role held by the Friends’ Association as ambassador and supporter has also been of central importance. The stated aims of the Association is to contribute financially and to increase public understanding of the orchestra’s cultural significance. Its contribution to encouraging this understanding is as important today as ever.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Already in the 1920s, the Oslo Philharmonic was aware of its duty to facilitate the discovery of classical music for younger listeners − during those years the orchestra’s schools concerts were a central part of this work. Later, the so-called Academic Concert Series was introduced.

From the 1952/53 season onwards, these youth concerts became an important bridge to a new generation of concertgoers. The newly established Friends of the Philharmonic Assocation was a strong partner from the two very first concerts, on 2 December 1952 and 3 February 1953.

Kristian Lange, who was known for his series of radio shows about music, took on the role as moderator, and the headline for the little concert series was “The Melody Which Became Something More; Music is not Mathematics”.

The youth concerts were a big enough success for the orchestra to justify extending the series to four concerts in subsequent seasons. After a little dip in interest, a conference and public survey were held towards the end of the decade in order to determine what young people themselves wanted to hear. This resulted in the concert A Challenge: From Mozart to Jazz.

Young people were asked which composers whose music they most wanted to hear. The results are summed up in the anniversary programme of the Oslo Philharmonic from 1969: Beethoven was mentioned by 116 people, Mozart by 102, Grieg by 76, Tchaikovsky by 69, Chopin by 63, Bach by 56 and so on.

The youth concerts continued with considerable success also into the 1960s. The young university lecturer Jon Medbøe became a permanent host, and his inspiring introductions to the concerts became well-known. The concerts continued to draw full houses until the 1970s.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

During the last year of the Second World War, in what would have been the concert season 1944/45, the orchestra did not perform any concerts of their own. The preceding season had already been very problematic for various reasons, and from May 1944 onwards, the occupying authorities agreed to suspend operations until further notice.

However, the orchestra gathered to play the last war year as well; it had, during the war, a parallel task as a radio orchestra in NRK. This activity continued almost into the peace of May 1945. The last concert of the "Radio Orchestra" was held April 29.

On 22 May 1945, the first board meeting after the war was held, with Johs. Berg-Hansen as Chairman. The Board’s first task was to make clearances in the orchestra’s ranks, and remove musicians who had collaborated with the German authorities during the war, as well as finding new ones to replace them with. Nine musicians were removed from their positions.

They did not have to remove one of these: German-born flute player Rolf Schüttauf, who before the war had appeared both as a soloist and composer in the orchestra’s concert programmes. During the war he grew to be a despised member of the German security force Gestapo. He was shot and killed by the Home Front in 1944.

On 8, 10 and 11 June, the orchestra took part in the anniversary concerts of the National Theatre, and on 12 June, the orchestra held its own anniversary concerts. Also these took place at the National Theatre, and both King Haakon, Crown Prince Olav and Crown Princess Märtha were present.

The orchestra’s new Principal Conductor, Odd Grüner-Hegge, conducted, and the orchestra played Johan Svendsen’s Symphony No. 2, extracts from Edvard Grieg’s music to Peer Gynt, Ludvig Irgens-Jensen’s Passacaglia, and Johan Halvorsen’s Norwegian Rhapsody No. 1.

On 10 September, the orchestra opened its first concert season following the war, with the first of forty-nine planned concerts. The audience was starved for music, and filled the concert hall for concert after concert. Composers both in Norway and abroad had grown a rich collection of new music to fill the orchestra’s programmes with.

“The Norwegian Music Week” was an important occasion in the autumn of 1945. Here, Norwegian composers were invited to present some of the music the public had missed during the war years. Symphonies by composers such as Klaus Egge, Harald Sæverud and Ludvig Irgens-Jensen were played for the first time.

New composer names from abroad were also presented: on 13 September 1945, music by British composer Benjamin Britten was on the programme for the first time: Les Illuminations for vocal soloist and orchestra. In the spring of 1946, Shostakovich’s fifth symphony and Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf were heard for the first time in Norway.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Edvard Grieg (1843−1907) was Director of the Music Association in 1871, one of the Oslo Philharmonic's most significant predecessors. By the establishment of the orchestra in 1919 he was, a mere decade after his death, still considered a national hero. His most famous piece for orchestra, his Piano Concerto in A-Minor, was played at the orchestra’s very first concert.

The first Grieg anniversary was in 1932, the twenty-fifth year marking the composer’s death. The planned memorial concert in early September had to be cancelled due to great economic difficulties for the orchestra. Fortunately, it was rescued, and the concert was held on 26 September, with king, queen, and the composer’s 86-year-old widow, Nina Grieg, in the audience.

“Thank God for that we are now saved from the shame it would have been, if Norway had been forced to let this day pass unmarked”, wrote Arne van Erpekum Sem in a comment following the concert, where the orchestra played Grieg’s Holberg Suite and his piano concerto.

The next big Grieg year, the centenary of his birth, in 1943, also presented great challenges, lack of funds being only one of these. During the war, concert operations had been a furiously debated topic, and the Oslo Philharmonic often found itself in the middle of the conflict.

After a while the public displayed different behaviour in relation to concerts arranged by the German-controlled broadcasting and the so-called “free concerts” the cultural institutions arranged themselves. The first were often played to empty halls, while the free concerts often attracted a good number of spectators.

It was therefore very significant for the Grieg anniversary in 1943, following a great deal of debate, that the concerts were arranged by the Oslo Philharmonic itself. Altogether five concerts were held, from 7-12 June, and the public attended in great numbers.

The Grieg anniversary as a whole was nevertheless perceived as compromised by the occupiers. The authorities spent large sums on the celebration and held a series of solemn events. The underground resistance movement viewed the anniversary as a scandal and sent out clear messages to musicians not to take part.

In spite of persistent attempts, the resistance didn't succeed in making the music scene as a whole boycott the authorities. And even if the orchestra was able to avoid compromises during the Grieg anniversary, the same cannot be said of the war years as a whole.

In their parallel work as a radio orchestra for NRK, the orchestra played on a number of events under the auspices of the occupying power. Most attention was given to the so-called State Act at Akershus, a ceremony for the Nazi takeover of power in Norway in 1942.

The orchestra's activities during the war years, together with the rest of the history of the Oslo Philharmonic, have been thoroughly covered in Alfred Fidjestøl's book Lyden av Oslo − Oslo-Filharmonien 1919−2019".

When the most important conductors in history are listed, Wilhelm Fürtwangler’s name is always among them. In 1922, at the age of thirty-six, he became Principal Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, a position he held for two periods for altogether twenty-five years.

Like all leading cultural personalities of the time, Fürtwangler was obliged to relate to the development of Nazism and its leaders. Due to the fact that he did not leave Germany until the end of the war, and conducted concerts arranged by the Nazis, he was heavily criticised and forbidden to perform following the end of the war.

Fortunately, he was declared innocent in the process which followed the war. Fürtwangler had actually been in conflict with the Nazis ever since they first rose to power, and had helped many Jews both before and during the Second World War. The most prominent of these defended him against the accusations.

Like his predecessor, Arthur Nikisch of the Berlin Philharmonic, Wilhelm Fürtwangler visited Oslo to conduct the Philharmonic Orchestra. The timing was remarkable: on 1 April 1940, German troops were preparing for the invasion of Norway, while the University Aula was packed with listeners who were there of their own free will, listening to the conductor direct a concert programme consisting of music by solely German-speaking composers.

The concert, which was broadcast on the radio, started with Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 88, followed by Richard Strauss’ Tod und Verklärung, and concluded with Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7. After several enthusiastic rounds of applause, an encore was performed: Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture.

“Fürtwangler was warmly lauded yesterday, from the bottom of our hearts. He was witness to that, in our country, in times such as this, the sole consideration is art”, wrote composer and critic Pauline Hall of the performance.

The orchestra managed one more concert before the breakout of war, on 8 April. The programme was very international, with music by J.S. Bach from Germany, W.A. Mozart from Austria, Zoltán Kodály from Hungary, Ture Rangström and Hugo Alfvén from Sweden, and Maurice Ravel from France.

Ironically enough, at the two first concerts after the breakout of war, on 28 April and 3 May, only Norwegian music was played.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

Christian Sinding turned 80 years old in the winter of 1936, and was at this point Norway’s most famous and celebrated composer. He had been wholeheartedly present throughout the orchestra’s first years: he had held a speech during its opening concert in 1919, and his music was frequently performed. His 70th birthday in 1926 was celebrated as enthusiastically as his 80th.

Both King Haakon and and the Crown Prince couple were present for his celebration concert on 11 March 1936. The main speech was held by the President of the Storting, C.J. Hambro, who handed the composer a large laurel wreath from the Norwegian people. The University Aula was packed full, and flowers and garlands adorned the walls.

Christian Sinding had experienced a slightly unsteady start to his career, but had a breakthrough as a composer in Norway in 1885. Some years later, he also experienced great success in Leipzig. His work for piano, Frühlingsrauschen, from 1897, made him world famous. In subsequent decades, he enjoyed a respected position as a composer internationally, especially in Germany, and became a national hero in his homeland. From 1924, he was given “Grotten” as an honorary residence.

Christian Sinding’s reputation took a steep downturn towards the end of his life. He fell ill and grew demented in his last years, and his enormous popularity made him attractive to the German authorities during the war. Eight weeks before his death in 1941, he became a member of Nasjonal Samling, the Norwegian far-right party. Little is known about what this really meant to him. In any case, it led to his music being removed from concert programmes after the war. Norway’s great composer hero was forgotten for a long period of time, and his reputation has never quite recovered.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

The first decades of the orchestra’s existence saw a number of financial ups and downs. One of the biggest dips occurred in 1932, when support from both city and state were heavily reduced. Musicians were forced to accept salary cuts in order to save the orchestra from financial ruin − and this wasn’t the first time.

Despite reduced salaries, the number of concerts increased in subsequent seasons. In 1934, a player entered the field who ensured a more stable foundation for operations: the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), which had been established in the preceding year.

The first regular radio broadcasts in Norway started in 1925, and were arranged by the privately owned Broadcasting Compnay. The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation was established on 1 July 1933, and had ninety employees. In the beginning, it broadcast on the radio from 10:00 until 22:45, with a break between 15:00 and 17:00.

In other words, there were many hours of radio which were to be filled every week, with generous space for music. The Oslo Philharmonic entered into a contract with the NRK as a permanent radio orchestra, with the obligation to twenty rehearsal hours and seventeen broadcast concert hours per week, which, combined with the rest of the orchestra work made for a tough schedule.

While the contract with the NRK rescued the orchestra from financial disaster, the easy access to music on the radio curbed the public interest in attending concerts somewhat. At any rate, ticket sales went down after the radio broadcasts started. In the long run, however, the availability of orchestral music on the radio is bound to have been a positive development. Listeners from far beyond the capital gained access to it, and orchestral music reached much broader targets than it had ever done before.

(Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa)

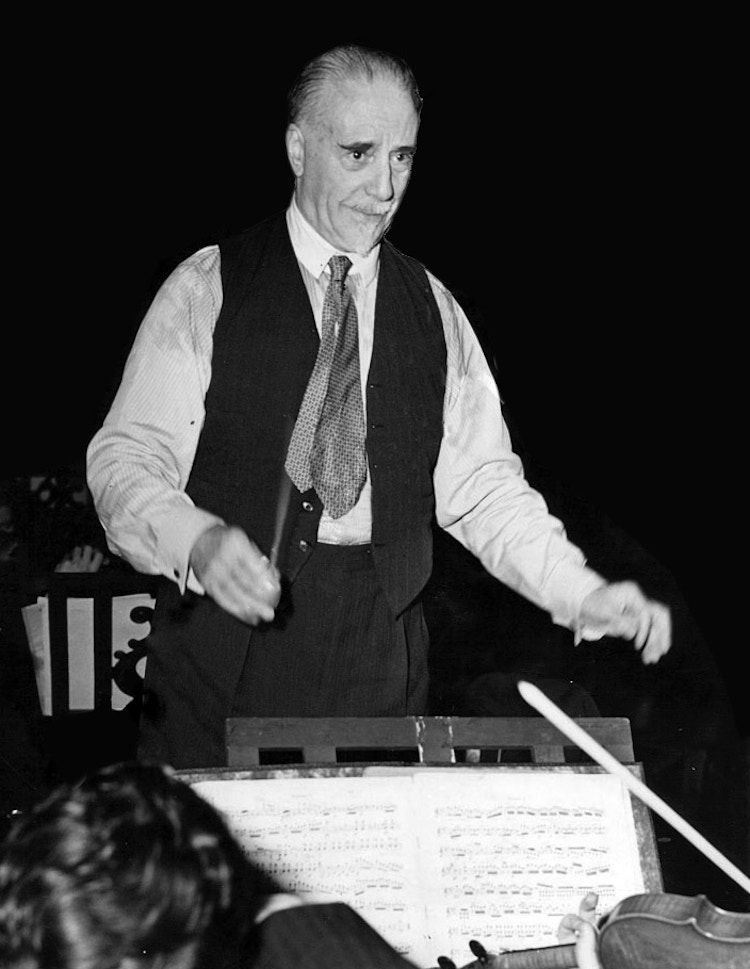

Odd Grüner-Hegge was born in Christiania in 1899 as the youngest of four brothers, and began playing the piano early. When he was six years old, Odd attended a concert where he saw Edvard Grieg himself perform. Following this, he declared that he wanted to become a composer.