Wagner Berg Brahms Nagano

A Concert for an Angel

A Concert for an Angel

Kent Nagano conducts Brahms’ mighty first symphony.

Acclaimed German violinist Veronika Eberle performs Alban Berg’s gripping Violin Concerto − the most beautiful monument of musical Modernism, written “in memory of an angel” by a composer who was himself facing death. Richard Wagner’s mystical, magical prelude to his opera Parsifal sets the tone for the evening.

G-D-A-E, E-A-D-G. The soloist starts her tribute by brushing the bow tenderly over the violin’s open strings, from the dark G string to the light E string and back again − in such a simple, innocent and vulnerable fashion as is possible on the instrument. The lyrical introduction in Alban Berg’s (1885−1935) Violin Concerto speaks of a composer who had other intentions that what music history has often attributed to him. This work is not about twelve-tone technique or Modernism, but about creating a gripping expression “in memory of an angel”.

Berg was not particularly motivated when the violinist Louis Krasner asked him to write a violin concerto in 1935. He wanted to devote all his time to working on Lulu − a work which after the composer’s death would becaome one of the 20th century’s epoch-defining operas. A tragic event was to give him the inspiration he needed. In April of 1935, Alma Mahler’s daughter, Manon Gropius, died, at the age of only eighteen. The following month, Berg put Lulu aside and started composing his violin concerto. Later the same year, he wrote to Alma, and asked if he could dedicate the work to Manon with the epithet “in memory of an angel”. Berg never managed to complete Lulu, and died himself, on the 23rd of December that very same year. His Violin Concerto was performed for the first time in Barcelona four months after his death, in April 1936, with Krasner as the soloist.

Berg’s use of tonal elements in an atonal landscape has ensured his Violin Concerto is one of the most frequently performed works from the Modernism of the Second Viennese School in the first half of the 20th century. The starting point for Berg is dodecaphony − a composition technique where all twelve of the scale’s chromatic tones are placed in a series which is treated in different ways. In his violin concerto, Berg mixes techniques of Modernism and atonality with characteristics and tones from the near and distant past. The most apparent of these are the references to the past, such as when Berg uses the chorale Es ist genug, written by J.S. Bach (1685−1750) towards the end of the concerto. The effect is incredibly gripping after the music has moved from the lyrical opening via a dancing allegro, to a violent, virtuosic and desperate cadenza. In the end, everything calms down, and the echoes of Berg and Bach continue to resonate in the listener’s memory.

The strikes of the timpani, restless syncopated rhythms, and a dramatic rising line in the strings and an equally dramatic sinking line in the woodwinds, all this played in a sinister C Minor − there is no doubting the seriousness of Johannes Brahms’ (1833−1897) Symphony No. 1. Maintained by his contemporaries to be Beethoven’s heir within the German symphonic tradition, Brahms must have felt somewhat under pressure. The composer’s own perfectionism and the heavy expectations of tradition were reasons he spent almost twenty years in writing his first symphony. When it was finally finished in 1876, Brahms received all the acknowledgement he could wish for: the symphony was lauded as “Beethoven’s tenth”.

In the middle of the 19th century, when Berlioz was composing programme symphonies and Liszt symphonic poems, many felt that the symphonic form had grown somewhat outdated. Brahms responded by continuing along the course Beethoven had carved out. Some of his contemporary critics felt the connections to his hero to be a little too strong, especially because a theme in the last movement of Brahms’ first symphony resembled a corresponding theme in Beethoven’s ninth. Brahms was evidently not embarrassed in the slightest by the similarity and retorted: “Yes, every idiot can hear that!”

As in Beethoven’s fifth, Brahms’ first symphony moves “from battle to triumph”. The solemnity of the beginning is balanced by two lighter movements, which create a contrast in expression but are still part of a greater symphonic development, before the triumph in the monumental finale. The sinister C Minor of the first movement is gradually transformed into C Major, and along the way, motives are developed in the best spirit of Beethoven, with a mastery of counterpoint worthy of Bach. Furthermore, the rhythmical complexity and grandiose symphonic construction of the work surpassed what his predecessors had produced, and the triumph ensured that Brahms became the third big “B” in the history of German music.

Brahms’ symphonies have always had a central place in the Oslo Philharmonic’s repertoire, and his first symphony was performed twice already in the orchestra’s first season. As is the case with our concerts in 2020, the concerts in April 1920 were conducted by an internationally acclaimed conductor − the outstanding Arthur Nikisch. Brahms once pronounced that Nikisch’s performance of Symphony No. 4 was “Quite exemplary. It’s impossible to experience it better”, and when Nikisch was due to appear in Oslo in 1920, Georg Schneevoigt, Principal conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic, wrote in the newspaper Morgenbladet:

“In the next days, Arthur Nikisch will be guesting in Christiania; a true artist who, in international music life, is of the very highest calibre. Yours truly allows himself to alert the public’s attention to the opportunity to experience this remarkable artist’s greatness in their own city. Nikisch’s personal contribution to the music life of our time is and has been of a transformative type. In him, the modern conductor finds his ideal.

Nikisch has a unique ability to spiritually as well as plastically develop different works of music. Amongst conductors living today, there is practically no one execpt him who has personally lived through and actively taken part in the period of German greatness in music, in close collaboration with the epoch’s greatest men, from Wagner to Liszt".

(Georg Schneevoigt, Morgenbladet, 20.04.1920)

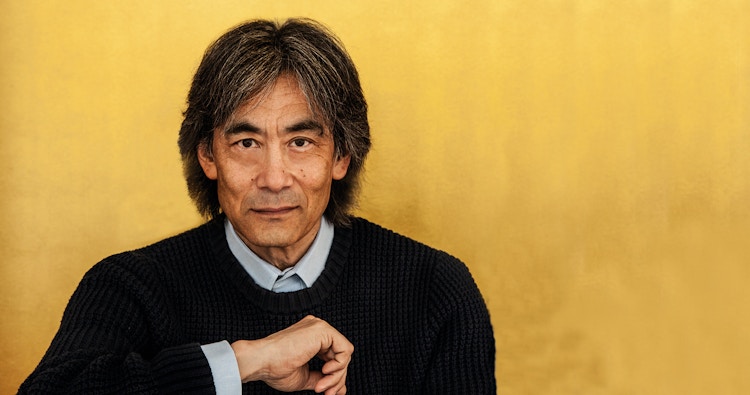

(Text: Thomas Erma Møller; Translation from Norwegian: Sarah Osa; In photo: Kent Nagano; Photo: Felix Broede)

What is played

- Richard Wagner Prelude from Parsifal

- Alban Berg Violin Concerto

- Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 1

Duration

Performers

-

Kent Nagano

Conductor -

Veronika Eberle

Violin

Tickets

Prices

| Price groups | Price |

|---|---|

| Adult | 120 - 490 NOK |

| Senior | 120 - 395 NOK |

| Student | 120 - 245 NOK |

| Child | 120 NOK |

Subscription

Wagner Berg Brahms Nagano